Incorporation/UnitedStates

NOTE: This is a simple overview for those not hugely familiar with the United States legal system to understand how its organized. It is also a good refresher for those who had US Politics many many years ago

The United States is subdivided into 50 states, 4 unincorporated organized territories, several unincorporated unorganized territories, and the District of Colombia. In a legal sense, it operates as fifty independent nations bound together under a federal government, similar in relation of the European Union and its member states. Territories are directly administrated by the federal government, and do not have representation in either the Congress or the Senate.

Separation between the federal government and the states is defined by the US Constitution, defining which powers are reserved by the federal government and those by the individual states. Unlike the European Union, the federal government can levy taxes across the union (under the concept of "Taxation Equals Representation"[1]) and represent the states collectively in international matters. Powers not granted to the federal government remain in the hands of the states. All states are bound to the US Constitution which operates as the highest law in the land.

With the exception of the State of Louisiana (which operates on the basis of civil law), both the federal government and the states operate under a system of common law. Common law is built on a combination of statute and case law, with case law in redefining, narrowing or widening statutes. Due to the relationship between the federal and state governments, case law is only binding to the jurisdiction in which it was founded. For instance, copyright laws are incorporated on a federal level, which means matters of copyright are to be decided in the federal courts system. As incorporation is handed on a state level, issues relating to it would be heard in that state's local courts.

State courts are organized by the constitution of the state, which defines their local system of courts. For the most part, states such as New York and California operate on the concept of a district court and an appellate court (sometimes referred to as a supreme court, such as the New York State Supreme Court). A specific state's court structure will be covered on an overview of that state.

Understanding Binding Judgements and Jurisdiction in the United States

As previously stated, its easier to think of the United States as fifty independent countries bound under the United States Constitution. States have large amounts of autonomy with respect to handling issues within their own borders, while the federal government is only normally only involved for issues in which it either has jurisdiction, or for issues that are disputed across state lines. To further complicate matters, federal appellate courts (the most common) are subdivided into circuits, which either cover a specific geographical area, or a specific topic of law. In the interests of sanity, this section is broken into Federal and State levels.

Who Has Jurisdiction?

Federal Jurisdiction is defined by 28 U.S. Code § 1332, 28 U.S. Code § 1331 and Article III, § 2 US Constitution.

In summary, an issue is a matter of federal jurisdiction if any of the following is true:

- If the matter in controversy exceeds the sum or value of $75,000, exclusive of interest and costs, and is between-

- Citizens of different states

- Those who are not residents of the United States

- If the plaintiff alleges a violation falling under federal jurisdiction

- These are matters involving the United States Constitution, federal law, or any treaties that the United States is involved in

For the purposes of this law, corporations are considered citizens in all states in which it is incorporated, or has a principle place of business. As we're likely to be involved with matters with respect to freedom of speech and press, it is likely that if we're hauled to court, any matter would be federal, not state.

For most cases involving privilege, disclosure of sources, etc., we can expect that almost all these cases will come on a state level; only 7% of such cases are decided on a federal level[2]. For issues related to the DCMA, copyright, and patents, as these privileges are defined by federal statue, they will always be argued on a federal level.

Federal Judiciary

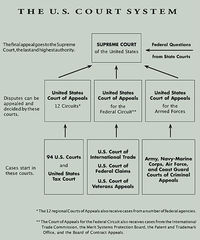

The Federal Judiciary operates on a three-tiered system, with cases starting in district courts, appealed to an appropriate appellate court, and then from there can be appealed to the Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS), which acts as the court of last resort.

As a common law system, much of the legal framework of the United States is defined in various court rulings vs. codified law. This is known as president, or case law. Somewhat counter-intuitive, case law is not binding automatically across all federal level courts. Case law decisions made by an appellate court only affects that individual circuit, and not the United States as a whole. Cases heard by SCOTUS however are binding on all courts on a federal level, and on state courts deciding matters of federal laws.

This creates the unique situation where it is possible for two appellate circuits to come to different decisions; this is known as a circuit split (recent court cases involving NSA wiretapping is an example of such). Such a split is grounds for SCOTUS to accept certiorari, and hear the case to set a final binding precedent.

District Courts

All cases in the federal system start at a district court. As of this writing, there are 97 district courts, one for each of the 94 federal districts, and 3 for territories, which collectively encompass the entirety of the United States. These courts cover a specific geographical area, and hear all cases originating within that area. District courts are responsible for determining issues of fact, and act as first venue for any federal-level legislation. Each of these courts are located within an appellate circuit; these appellate circuits are the second level of appeals for all cases that originate within their confines.

Appellate Courts

United States Courts of Appeals is organized into 13 circuits; there are 11 numbered courts covering various geographical areas of the United States, one for the District of Columbia, and one Federal Circuit. The Federal Circuit is unique as it hears cases based on subject matter vs. cases locating from a specific geographic region; its jurisdiction is defined in 28 U.S. Code § 1295.

Although the federal circuit encompasses a large number of various subjects, for most matters, the only cases where we may become involved are those relating to trademark and patent law. Furthermore, decisions made by the Federal Circuit are binding on all distract level courts in which it has appellate authority. In other words: for matters of patents and trademarks; the Federal Circuit sets precedent across the entirety of the United States.

Supreme Court of the United States

SCOTUS is the highest court throughout the United States. For SCOTUS to hear a case, it must have already been heard through either the state courts, or through the federal courts. An application for the Supreme Court to hear a case is known as a writ of certiorari, however, there is no obligation for SCOTUS to accept such writs.

State Jurisdiction

For issues not meeting federal jurisdiction, the issue falls to state courts to resolve. Within state courts, the laws of the state are the primary rule of the land. The Fourteenth Amendment defines that the protections and rights of the constitution must be adhered to on a state level; for cases related to the protection granted under the constitution, state courts may rule based on statue defined in their state, case law of their state, and ruling of SCOTUS.[3]

As each state independently defines their own system of courts, there is no general guidelines I can place here. For states reviewed in-depth, I've included a summary of their local courts systems in that section. However, in general, most states are modelled similarly to the United States, with a district or local court, an appellate court, and a court of last appeals (sometimes, and confusing called a supreme court).

Legal Protections for Freedom of Speech and Press

Freedom of speech and press in the United States descend from the first amendment to the United States Constitution.

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

The First Amendment itself is applied to the states via the Fourteenth Amendment Section 1, reproduced below:

Section 1. All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.

Over the course of two centuries, the courts have constantly re-affirmed this right but have defined exceptions to protected speech and protected press. These exceptions as of today are:

- Obscenity (as defined by the Milter Test)

- Pornography

- Defamation (defined New York Times Co. v. Sullivan; very limited)

- Commercial Speech (partially; only when done for profit, see below)

- Illegal Transactions (United States v. Williams)

A summary of various cases cited here followed.

Near v. Minnesota (1931)

- Decided in: Supreme Court of the United States

- Holding: Prior restraint is only permissible in cases of "exceptional circumstances"

- Wikipedia Summary: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Near_v._Minnesota

- Judgement (original text): http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?court=us&vol=283&invol=697

Near v. Minnesota dealt with the question of prior restraint on publications; specifically, can the statute, or the government prevent the publication of something, and if so, under what grounds can it do so, and provided a key guideline with respect to the ability to restrain publications. It was cited heavily during New York Times Co. v. United States in deciding the judgement of that case.

Background

Jay M. Near and Howard A. Guilford, a resident of Minneapolis began to run his own newspaper called "The Saturday Post" who claims that various gangs were in fact running the city, including then future governor Floyd B. Olson. Articles from The Saturday Post were used to successfully prosecute at least one gangster called Big Moose Barrnett. Olson filed a complaint against Near and Guilford under Minnesota's Public Nuisance Law, in an attempt to silence the paper. The relevant section of this law was quoted in the Supreme Court brief:

Section 1. Any person who, as an individual, or as a member or employee of a firm, or association or organization, or as an officer, director, member or employee of a corporation, shall be engaged in the business of regularly or customarily producing, publishing or circulating, having in possession, selling or giving away.

'(a) an obscene, lewd and lascivious newspaper, magazine, or other periodical, or

'(b) a malicious, scandalous and defamatory newspaper, magazine or other periodical,

-is guilty of a nuisance, and all persons guilty of such nuisance may be enjoined, as hereinafter provided.

Using Section 1(b) as justification to censor the paper, Olson filed a case in Minnesota. After battling it out in state courts, the case eventually made its way to the Supreme Court

Findings

The Supreme Court found that the First Amendment, via the Fourteenth Amendment, provided no grounds for censorship or prior restraint, regardless of the truth of the news itself. From the holding itself:

For these reasons we hold the statute, so far as it authorized the proceedings in this action under clause (b) [283 U.S. 697, 723] of section 1, to be an infringement of the liberty of the press guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. We should add that this decision rests upon the operation and effect of the statute, without regard to the question of the truth of the charges contained in the particular periodical. The fact that the public officers named in this case, and those associated with the charges of official dereliction, may be deemed to be impeccable, cannot affect the conclusion that the statute imposes an unconstitutional restraint upon publication.

However, an exception was also defined in the same holding that restraint is permissible in 'exceptional cases', such as posting times of troop movements, or military orders in times of wars.

The objection has also been made that the principle as to immunity from previous restraint is stated too [283 U.S. 697, 716] broadly, if every such restraint is deemed to be prohibited. That is undoubtedly true; the protection even as to previous restraint is not absolutely unlimited. But the limitation has been recognized only in exceptional cases. 'When a nation is at war many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.' Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47, 52 , 39 S. Ct. 247, 249. No one would question but that a government might prevent actual obstruction to its recruiting service or the publication of the sailing dates of transports or the number and location of troops. [6] On similar grounds, the primary requirements of decency may be enforced against obscene publications. The security of the community life may be protected against incitements to acts of violence and the overthrow by force of orderly government. The constitutional guaranty of free speech does not 'protect a man from an injunction against uttering words that may have all the effect of force. Gompers v. Buck's Stove & Range Co., 221 U.S. 418, 139 , 31 S. Ct. 492, 34 L. R. A. (N. S.) 874.' Schenck v. United States, supra.

Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969)

- Decided in: Supreme Court of the United States

- Holding: Ohio state law about inflammatory speech fails imminent lawless action

- Wikipedia Summary: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_Times_Co._v._United_States

- Judgement (original text): http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/scripts/getcase.pl?court=us&vol=395&invol=444

Brandenburg v. Ohio defined a specific test in dealing with when inflammatory speech ceases to be protected speech; this is important because it defines the legal grounds where we may be forced to remove content from the site and setting a baseline on what we can and can't have on the site.

Summary

Clarence Brandenburg, a member of the KKK clan, invited a reporter from a Cincinnati television station to come and film a rally. The rally as filmed show cross burning, obsecities and hatred targeted at various minorities and the United States itself. Brandenburg was charged advocating violence under an Ohio's criminal syndicalism statute. The Ohio courts system affirmed the decision, but SCOTUS accepted the case.

Holding

At the time, the Untied States operated under the "clear and present danger" test, which was defined in Whitney v. California[4][5] which defined inflammatory speech as "by utterances inimical to the public welfare, tending to incite crime, disturb the public peace, or endanger the foundations of organized government and threaten its overthrow.", which further court ruling refined into the "Bad Tendency test" test. Brandenburg v. Ohio replaced this a far more strict standard, known as the imminent lawless action test.

As defined by the court, for speech to be considered inflammatory (and thus not protected by the first amendment), it must meet three criteria, specifically, it must have a specific criminal intent, that such actions were imminent, and that it was likely that people would act on it. Justices Black and Douglas wrote a concurrence that went as far as to say that "falsely shouting fire in a crowded theatre" was probably the only type of speech that would be prosecutable under this test.

New York Times Co. v. United States (1971)

- Decided in: Supreme Court of the United States

- Holding: Prior restraint requires proof of "grave and irreparable" damage

- Wikipedia Summary: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_York_Times_Co._v._United_States

- Judgement (original text): https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/403/713/case.html

New York Times Co. v. United States was a re-affirmation of Near v. Minnesota, as well as strongly defining the test of prior restraint as applied to the United States government. It also re-affirms that publication of classified materials by newspapers is not inherently illegal. The case itself revolves around the publication of the [[1] Pentagon Papers]], a then-classified report which revealed that several successive administrations had mislead the American public and the Congress with its actions during the Vietnam War.

Summary

Daniel Ellsberg, an aide to Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, and his friend Anthony Russo decided to leak a report detailing the real reasons the United States were involved in Vietnam to The New York Times after becoming disillusioned with the war, and after internal efforts at whistle-blowing were unheeded. The report, formally titled United States – Vietnam Relations, 1945–1967: A Study Prepared by the Department of Defense became known as the Pentagon Papers after The New York Times began a publication of articles revealing the dirty truth behind the war. Sitting President Richard Nixon was convinced to prosecute Ellsberg for leaking the papers, and to force the New York Times to cease publication after the paper refused a voluntary request.

Ellsberg also gave copies of the report to the Washington Post which began running its own articles. In an attempt to stop publication, Attorney General John N. Mitchell obtained an injunction against the paper, citing Section 793 of the Espionage Act as justification. A massive law, only one small section of the Espionage Act provided the justification to censor the paper:

(e) Whoever having unauthorized possession of, access to, or control over any document, writing, code book, signal book, sketch, photograph, photographic negative, blueprint, plan, map, model, instrument, appliance, or note relating to the national defense, or information relating to the national defense which information the possessor has reason to believe could be used to the injury of the United States or to the advantage of any foreign nation, willfully communicates, delivers, transmits or causes to be communicated, delivered, or transmitted, or attempts to communicate, deliver, transmit or cause to be communicated, delivered, or transmitted the same to any person not entitled to receive it, or willfully retains the same and fails to deliver it to the officer or employee of the United States entitled to receive it.[6]

.

The newspaper appealed the decision. The lower courts upheld the injection against the New York Times, causing the paper to appeal to the Supreme Court, which accepted certiorari and merged this case, and a second case against the Washington Post into New York Times Co. v. United States.

Findings

The Supreme Court found in favor of the New York Times, defining a test of "grave and irreparable" for prior restraint. As written by Justice White

The Government's position is simply stated: The responsibility of the Executive for the conduct of the foreign affairs and for the security of the Nation is so basic that the President is entitled to an injunction against publication of a newspaper story whenever he can convince a court that the information to be revealed threatens "grave and irreparable" injury to the public interest; [2] and the injunction should issue whether or not the material to be published is classified, whether or not publication would be lawful under relevant criminal statutes enacted by Congress, and regardless of the circumstances by which the newspaper came into possession of the information.

.[7]

Justice Black wrote a rather insightful piece about why the court ruled against injunction. I've included it here as it captured the full essence of the significance of this case, as well as the role of the courts in acting as checks and balances.

MR. JUSTICE BLACK, with whom MR. JUSTICE DOUGLAS joins, concurring.

I adhere to the view that the Government's case against the Washington Post should have been dismissed and that the injunction against the New York Times should have been vacated without oral argument when the cases were first presented to this Court. I believe [403 U.S. 713, 715] that every moment's continuance of the injunctions against these newspapers amounts to a flagrant, indefensible, and continuing violation of the First Amendment. Furthermore, after oral argument, I agree completely that we must affirm the judgment of the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and reverse the judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit for the reasons stated by my Brothers DOUGLAS and BRENNAN. In my view it is unfortunate that some of my Brethren are apparently willing to hold that the publication of news may sometimes be enjoined. Such a holding would make a shambles of the First Amendment.

Our Government was launched in 1789 with the adoption of the Constitution. The Bill of Rights, including the First Amendment, followed in 1791. Now, for the first time in the 182 years since the founding of the Republic, the federal courts are asked to hold that the First Amendment does not mean what it says, but rather means that the Government can halt the publication of current news of vital importance to the people of this country.

In seeking injunctions against these newspapers and in its presentation to the Court, the Executive Branch seems to have forgotten the essential purpose and history of the First Amendment. When the Constitution was adopted, many people strongly opposed it because the document contained no Bill of Rights to safeguard certain basic freedoms. [1] They especially feared that the [403 U.S. 713, 716] new powers granted to a central government might be interpreted to permit the government to curtail freedom of religion, press, assembly, and speech. In response to an overwhelming public clamor, James Madison offered a series of amendments to satisfy citizens that these great liberties would remain safe and beyond the power of government to abridge. Madison proposed what later became the First Amendment in three parts, two of which are set out below, and one of which proclaimed: "The people shall not be deprived or abridged of their right to speak, to write, or to publish their sentiments; and the freedom of the press, as one of the great bulwarks of liberty, shall be inviolable." [2] The amendments were offered to curtail and restrict the general powers granted to the Executive, Legislative, and Judicial Branches two years before in the original Constitution. The Bill of Rights changed the original Constitution into a new charter under which no branch of government could abridge the people's freedoms of press, speech, religion, and assembly. Yet the Solicitor General argues and some members of the Court appear to agree that the general powers of the Government adopted in the original Constitution should be interpreted to limit and restrict the specific and emphatic guarantees of the Bill of Rights adopted later. I can imagine no greater perversion of history. Madison and the other Framers of the First Amendment, able men [403 U.S. 713, 717] that they were, wrote in language they earnestly believed could never be misunderstood: "Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom … of the press … ." Both the history and language of the First Amendment support the view that the press must be left free to publish news, whatever the source, without censorship, injunctions, or prior restraints.

In the First Amendment the Founding Fathers gave the free press the protection it must have to fulfill its essential role in our democracy. The press was to serve the governed, not the governors. The Government's power to censor the press was abolished so that the press would remain forever free to censure the Government. The press was protected so that it could bare the secrets of government and inform the people. Only a free and unrestrained press can effectively expose deception in government. And paramount among the responsibilities of a free press is the duty to prevent any part of the government from deceiving the people and sending them off to distant lands to die of foreign fevers and foreign shot and shell. In my view, far from deserving condemnation for their courageous reporting, the New York Times, the Washington Post, and other newspapers should be commended for serving the purpose that the Founding Fathers saw so clearly. In revealing the workings of government that led to the Vietnam war, the newspapers nobly did precisely that which the Founders hoped and trusted they would do.[8]

Branzburg v. Hayes (1972)

- Decided in: Supreme Court of the United States

- Holding: Prior restraint requires proof of "grave and irreparable" damage

- Wikipedia Summary: The First Amendment's protection of press freedom does not give a reporters privilege in court, but specific requirements must be meet before "reporter's privellege" can be breached.

- Judgement (original text): http://supreme.justia.com/us/408/665/case.html

NOTE: While this case appears to be a blow for freedom of press, its been interpreted by the lower courts that reports privellege exists, and that courts must decide on a case-by-case basis if such protections are warranted in a case.

Branzburg v. Hayes dealt with the issue of "reporters privilege", or the right not to divulge sources, and defined a test for when the government can force a reporter to name his sources in a court of law. Specifically, the government must "convincingly show a substantial relation between the information sought and a subject of overriding and compelling state interest". This has further been

Background

This section copied from Wikipedia'

Paul Branzburg of The (Louisville) Courier-Journal, in the course of his reporting duties, witnessed people manufacturing and using hashish. He wrote two articles concerning drug use in Kentucky. The first featured unidentified hands holding hashish, while the second included marijuana users as sources. These sources requested not to be identified. Both of the articles were brought to attention of law-enforcement. Branzburg was subpoenaed before a grand jury for both of the articles. He was ordered to name his sources.

Earl Caldwell, a reporter for The New York Times, conducted extensive interviews with the leaders of The Black Panthers, and Paul Pappas, a Massachusetts television reporter, who also reported on The Black Panthers, spending several hours in their headquarters were similarly subpoenaed around the same time as Branzburg.

All three reporters were called to testify before separate grand juries about illegal actions they might have witnessed. They refused, citing privilege under the Press Clause, and were held in contempt.

Findings

The court ruled against Branzburg, ordering him to compel his sources. In the judgement however, Justice Powell wrote the following which has been a guiding test for determining if/when a reporter's privilege applies or doesn't as the case may be. The New York Times summarized his words as follows:

In contrast to his meandering concurrence, the few crisp sentences of notes were relatively clear. “We should not establish a constitutional privilege,” Justice Powell said, referring to one based on the First Amendment. Such a privilege would create problems “difficult to foresee,” among them “who are ‘newsmen’ — how to define?” But, he added, “there is a privilege analogous to an evidentiary one” — like those protecting communications with lawyers, doctors, priests and spouses — “which courts should recognize and apply” case by case “to protect confidential information.”

Recognition of Bloggers/New Media as Journalists

The Department of Justice, most of the judicial circuits, and 40 states[10] recognize reporter's privilege, or the ability to not be compelled to release their sources, and there have been efforts to pass a federal shield law[11][12] However, the specific definition of who is and who is not a journalist remains undecided.

The issue is if bloggers, freelance journalists, and other individuals writing for non-traditional media qualifies for Freedom of Press protection. This remains unanswered on a federal level. As of this writing, I'm [who?] unaware of any federal cases in determining the legal status, however, the issue has been argued twice in New Hampshire, and in Oregon with different verdicts. As states have the ability to provide stronger first amendment protections beyond those in the US Constitution, and those provided by the federal government, these cases provide strong arguments for (or against) incorporation in their respective states.

The Mortgage Specialists, Inc. v. Implode-Explode Heavy Industries, Inc. (2010 - New Hampshire)

- Decided In: New Hampshire State Supreme Court

- Binding: Courts in New Hampshire

- Holding: Shield laws apply to online publications

- Wikipedia Summary: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Mortgage_Specialists,_Inc._v._Implode-Explode_Heavy_Industries,_Inc.#Reaction

- Judgement (original text): http://www.courts.state.nh.us/supreme/opinions/2010/2010041mortg.pdf

This is one of the most important legal cases with respect to sites like ours. I urge people to research and study this case in more detail. It deals with a user on the website posting comments and a loan chart that appears to have been sourced from The Mortgage Specialists. A similar situation for us would be if an AC (Anonymous Coward; i.e. non-registered user) posts on our site as either submitted content or comments that we run that act as an inside scoop.

Background

The judgement holds a very good summary of events, so I'm quoting it here

The record supports the following facts. Mortgage Specialists is a mortgage lender. Implode operates a website, www.ml-implode.com, that ranks various businesses in the mortgage industry on a ranking device that it calls “The Mortgage Lender Implode-O-Meter.” On its website, Implode identifies allegedly “at risk” companies and classifies them as either “Imploded Lenders” or “Ailing/Watch List Lenders.” The website allows visitors who register on the site and create usernames to post publicly viewable comments about lenders.

In August 2008, Implode published an article that detailed administrative actions taken by the New Hampshire Banking Department against Mortgage Specialists. In this article, Implode posted a link to a document that purported to represent Mortgage Specialists’ 2007 loan figures (Loan Chart). In response to the article, an anonymous website visitor with the username “Brianbattersby” posted two comments regarding Mortgage Specialists and its president.

After Mortgage Specialists became aware of the article and postings, it petitioned for injunctive relief, alleging that publication of the Loan Chart was unlawful because it violated RSA 383:10-b (2006) (mandating confidentiality of all investigative reports and examinations by the New Hampshire Banking Department) and that Brianbattersby’s postings were false and defamatory. Mortgage Specialists requested that Implode immediately remove the Loan Chart and postings from its website. Mortgage Specialists further demanded that Implode disclose both the identity of Brianbattersby and the source of the Loan Chart.

The trial court ruled in favor of Mortgage Specialists, but Implode appealed the case to the New Hampshire State Supreme Court.

Findings

IMPORTANT: This case was decided on a state level, NOT a federal level, so federal cases act as guidance, and are not necessary binding on the lower courts. Please keep this in mind. Please see the New Hampshire section for more information on specific laws and protections that are relevant to it

The New Hampshire Supreme Court found that Implode qualified for protection under the newsgathering privilege, and that they were protected under New Hampshire's shield laws.

Implode argues that the newsgathering privilege under Part I, Article 22 of the New Hampshire Constitution protects the identity of the source of the Loan Chart.

Obsidian Finance Group, LLC v. Cox (2011 - Federal/Oregon)

- Decided In: United States District Court for the District of Oregon

- Binding: State of Oregon (Appellate Division - Ninth Circuit)

- Holding: Cox denied media shield protections under the bias of "not a journalist"

- Wikipedia Summary: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Obsidian_Finance_Group,_LLC_v._Cox

- Judgement (original text): http://ia700403.us.archive.org/9/items/gov.uscourts.ord.101036/gov.uscourts.ord.101036.123.0.pdf

NOTE: This case is being appealed and working its way through the courts system. As of 04/25/2014, until the appellate court has ruled, this judgement is only binding on the state of Oregon. If appeals fail, the judgement will be valid across the Ninth Circuit unless SCOTUS accepts a writ of certiorari

Laws and Regulations Relating To The Operation Of A Website

CHECKME: This list is likely incomplete

Child Online's Privacy Protection Act (COPPA Regulations)

COPPA[13] is a series of laws, as the name suggestions, at protecting the privacy of children (defined in the statue as those under 13). In short, it requires parental consent to collect any sort of personal information for those under the age of 13, and defines the type of information sites can collect, retention, how its used, etc.

CHECKME: We don't require any information beyond an email to sign up; and reasonably, we could even loose that, but this might be considered 'personal information' under the law. Check various COPPA statues/sites, the law is unclear, and there's a supreme court site related to COPPA and non-profits

Online Copyright Infringement Liability Limitation Act (DCMA Title IV)

Passed as part of the DCMA, the OCILA provides the framework and mechanisms for take-down notices of infringing content, as well defining the "safe harbor" provisions for online service providers (OSP). To be protected from liability sites must conform to the posted regulation and requirements, as well as comply with all takedown and counter-takedown notices. These are defined under 17 U.S. Code § 512[14]; those relevant to us are listed below.

§ 512(d) Information Location Tools Safe Harbor

We're not held liable for people posting links on our website to various infringing material.

(d) Information Location Tools.— A service provider shall not be liable for monetary relief, or, except as provided in subsection (j), for injunctive or other equitable relief, for infringement of copyright by reason of the provider referring or linking users to an online location containing infringing material or infringing activity, by using information location tools, including a directory, index, reference, pointer, or hypertext link, if the service provider—

(1) (A) does not have actual knowledge that the material or activity is infringing; (B) in the absence of such actual knowledge, is not aware of facts or circumstances from which infringing activity is apparent; or

(C) upon obtaining such knowledge or awareness, acts expeditiously to remove, or disable access to, the material;

In short, when we are notified that something is infringing (aka, we get a takedown notice), if we remove it promptly, we're protected.

§ 512(h) Identify infringers.

There's two largely important sections for copyright holders (i.e., if someone posts copyrighted texts to the site; this happened on the other site). Section 1 defines the right, Section 3 defines what we have to turn over.

NOTE: The law here is vague, and is unclear if we need to collect things such as IP addresses and such to be "in compliance". As far as I can tell, nothing mandates that we collect IPs per se.

(1) Request.— A copyright owner or a person authorized to act on the owner’s behalf may request the clerk of any United States district court to issue a subpoena to a service provider for identification of an alleged infringer in accordance with this subsection.

This basically defines the ability to subpoena IP addresses on behalf of copyright holders.

(3) Contents of subpoena.— The subpoena shall authorize and order the service provider receiving the notification and the subpoena to expeditiously disclose to the copyright owner or person authorized by the copyright owner information sufficient to identify the alleged infringer of the material described in the notification to the extent such information is available to the service provider.

NOTE: This is the part that concerns me.

§ 512(i) Conditions for Eligibility

This section basically boils down to a checklist of things we need to do to qualify for safe harbor protections. To qualify, if a specific IP or account repeatedly infringes on the site, then we need to terminate the account and/or ban the IPID explain.

(1) Accommodation of technology — The limitations on liability established by this section shall apply to a service provider only if the service provider—

(A) has adopted and reasonably implemented, and informs subscribers and account holders of the service provider’s system or network of, a policy that provides for the termination in appropriate circumstances of subscribers and account holders of the service provider’s system or network who are repeat infringers; and

(B) accommodates and does not interfere with standard technical measures.

Section (m) Protection of Privacy

CHECKME: I need a legalese decoder on this one. From my reading of this, we only need to collect information to apply section (i); aka a banhammer, and have a method to delete.

(m) Protection of Privacy.— Nothing in this section shall be construed to condition the applicability of subsections (a) through (d) on—

(1) a service provider monitoring its service or affirmatively seeking facts indicating infringing activity, except to the extent consistent with a standard technical measure complying with the provisions of subsection (i); or

(2) a service provider gaining access to, removing, or disabling access to material in cases in which such conduct is prohibited by law.

Employment of Non-Citizens

CHECKME: This section needs a massive amount of vetting by both lawyers and accountants, as the laws relating to hiring someone who will not reside within the United States is extremely complex; most statutes operate on the basis of someone intending to immigrate to the United States.

Challenges And Concerns Operating Within The United States

This section goes through various concerns with regards to civil rights and freedoms that are likely to be a cause of concern. While the United States has strong protection of the press, many have voiced concerns with issues such as National Security Letters, NSA Wiretapping, etc. This section acts as a hilight reel of said concerns, and what we can do to protect ourselves

National Security Letters

National Security Letters (NSL) are a special type of subpoena issued by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, authorized under 18 U.S.C. § 2709, for purposes of "to protect against international terrorism or clandestine intelligence activities". Although they were originally created in 1978, NSLs in their current form were created by provisions of PATRIOT act. National Security Letters act as a type of "supergag" order, preventing parties receiving them from disclosing their existence. However, those who are served NSLs are able to appeal them, such as the case Doe v. Gonzales, and American Civil Liberties Union v. Ashcroft

NSLs have been challenged several times in court, and several battles have been won limiting the scope and power of NSLs; see: 2013 in Review: EFF Convinces Court to Declare National Security Letters Unconstitutional - President's Panel Agrees.

While NSLs still remain legal for the time being, and we would not be able to disclose the existence of an NSL, it is believed that is impossible to compel someone to lie. From this reasoning, a Warrant Canary could be created and periodically updated so as to affirm that we have NOT received a NSL. We could then stop updating the canary if we are served with an NSL. The warrant canary has, however, never been challenged in a court of law.

NSA Wiretapping

Incorporation as a Not-For-Profit

With the exception of non-for-profits (NFPs) created within the District of Columbia, all NFPs are created on a state level, then apply for tax-exempt status from the federal government. Under 28 U.S. Code § 1332, 28 U.S, corporations are essentially considered citizens in the state they're incorporated in, as well as states they primarily do business in. State laws define the requirements for incorporation, requirements of reporting for non-for-profit, as well as rules and regulations that a business must adhere to. This subset of states were selected based on either my personal familiarity with them, or on relevant state statute that increase our protections and freedom.

Due to strong local protections, and friendly decisions in the First Appellate Circuit, our first choice for incorporation shall be the state of New Hampshire.

New Hampshire

With an official slogan of "Live Free or Die", New Hampshire is well-known for its strong protections of individuals and preserving civil liberties. A politically active and liberal state, it is also known for the New Hampshire Primary, which is the first primary election United States presidential primary - Schedule for anyone seeking election to the office of the President in the United States.

At A Glance

- Appellate Circuit: 1st Circuit of Appeals

- Capital: Concord, NH

- Highest Court: New Hampshire Supreme Court

Favorable Statute And Case Law

New Hampshire enshrines freedom of press within its constitution, as well as having extremely favorable laws and statutes relating to press organizations.

OPINION OF THE JUSTICES No. 7787

The Mortgage Specialists, Inc. v. Implode-Explode Heavy Industries, Inc

This case was described as part of the overview for freedom of protection and press.

Requirements for Incorporation

The State of New Hampshire provides considerable documentation for forming a business, both profit and non-profit. The state provides a fairly comprehensive guide on incorporation. Non-profits can be formed by five individuals, and the guide defines the requirements of the bylaws and such.

While NH law does not provide for a specific "journalism" grounds for NFP, it does allow for any organization that would qualify for 501(c)(3) status to incorporate. The Statehouse News Online organization is a recognized 501(c)(3) organization for non-for-profit journalism, and as such we can use that as grounds to incorporate.

Articles of Agreement

Under NH, bylaws must meet the requirements of the articles of agreement. RSA 292:2 define these requirements

- The name of the corporation.

- The object for which the corporation is established.

- The provisions for establishing membership and participation in the corporation.

- The provisions for disposition of the corporate assets in the even t of dissolution of the corporation, including the prioritization of rights of shareholders and members to corporate assets.

- The address at which the business of the corporation is to be carried on.

- The amount of capital stock, if any, or the number of shares or membership certificates, if any, and provisions for retirement, reacquisition and redemption of those shares or certificates.

- The articles of agreement may contain a provision eliminating or limiting the personal liability of a director, an officer, or both, to the corporation or its shareholders for monetary damages for breach of fiduciary duty as a director, an officer, or both, except with respect to:

- Any breach of the director's or officer's duty of loyalty to the corporation or its shareholders.

- Acts or omissions which are not in good faith or which involve intentional misconduct or a knowing violation of law.

- Any transaction from which the director, officer, or both, derived an improper personal benefit.

- This paragraph shall not be construed to eliminate or limit the liability of a director, an officer, or both, for any act or omission occurring before January 1, 1992.

Who Can Be A Member

CHECKME: I don't see specific requirements for this, lawyer vetting required.

Taxes Levied

New Hampshire does not levy income or sales taxes.

References

* US Constitution Article I, § 8 * Article III of the Constitution (courts organization) * Ninth Amendment * 14th amendment

- ↑ Declaration of Independence

- ↑ REPORTER’S PRIVILEGE COMPENDIUM - http://www.rcfp.org/rcfp/orders/docs/privilege/NH.pdf

- ↑ http://www.rcfp.org/rcfp/orders/docs/privilege/NH.pdf

- ↑ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Whitney_v._California

- ↑ http://laws.findlaw.com/us/274/357.html

- ↑ 18 U.S.C. § 793 : US Code - Section 793: Gathering, transmitting or losing defense information

- ↑ http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/cgi-bin/getcase.pl?court=us&vol=403&invol=713

- ↑ http://caselaw.lp.findlaw.com/cgi-bin/getcase.pl?court=us&vol=403&invol=713

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2007/10/07/weekinreview/07liptak.html?_r=2&ex=1349496000&en=f6d6ce9bcf534225&ei=5088&partner=rssnyt&emc=rss&oref=slogin&

- ↑ http://www.rcfp.org/browse-media-law-resources/news-media-law/news-media-and-law-summer-2011/number-states-shield-law-cl

- ↑ From Wikipedia originally - H.R. 581 (Free Flow of Information Act of 2005). This bill has been referred to the House Committee on the Judiciary. See also S. 340 (Free Flow of Information Act of 2005) (referred to the Senate Committee on the Judiciary).

- ↑ From Wikipedia - S. 369. Sen. Dodd introduced the same bill in the 2004 congressional session. It was not acted on before the Senate adjourned. See S. 3020, 108th Congress, 2nd Sess. (2004); see also Second shield bill introduced in U.S. Senate, http://www.rcfp.org/news/2005/0217-con-second.html.

- ↑ 15 U.S.C. §§ 6501

- ↑ www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/17/512